A part of FEV Group

Humanoid robotics – E/E architecture, software and safety

Author -

FEV.io

Published -

Reading time -

4 mins

A part of FEV Group

Author -

FEV.io

Published -

Reading time -

4 mins

Humanoid robots are rapidly moving from the realm of a temporary hype to becoming a potential disruptor across multiple industries. Unlike traditional industrial robots, humanoid systems offer significantly greater flexibility in unstructured environments thanks to their human‑like form factor, enabling a broad spectrum of potential applications.

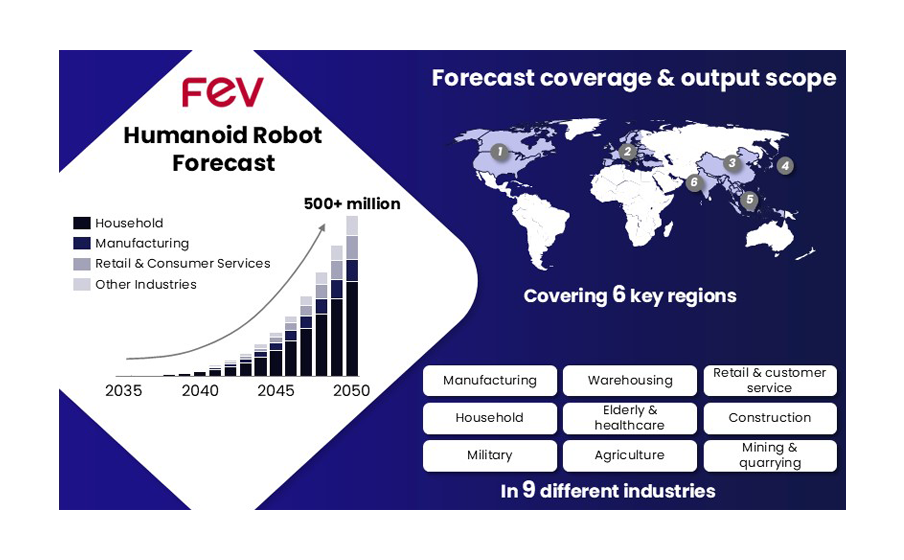

Based on a structured S-curve adoption model approach, FEV’s market projections indicate that more than 500 million humanoid robots could be deployed worldwide by 2050 across nine key industries and six global regions. Early adoption is expected in manufacturing, retail, and service sectors, followed by widespread integration in household applications. Substantial acceleration in market growth is anticipated after 2040.

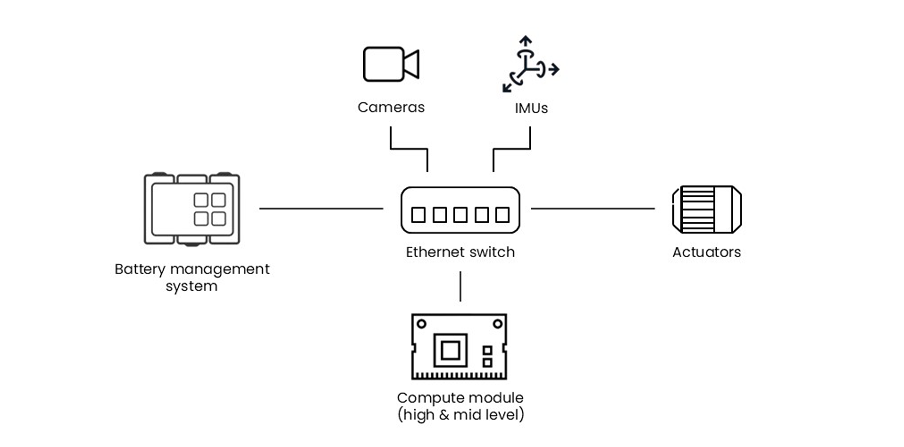

The electrical and electronic (E/E) architecture of humanoid robots typically comprises the on-board computing system, sensor suite, and elements of the energy system (see Figure 2). The on-board computing is commonly structured into three hierarchical levels:

The sensor suite generally includes cameras, inertial measurement units (IMUs), actuator encoders, force / torque sensors, and tactile sensors. Current industry trends in humanoids point toward full 360° visual coverage, often complemented by at least one forward-facing stereo camera, as well as the increasing integration of torque sensing directly within the actuators.

The energy system primarily encompasses the battery and its associated battery management system (BMS), which ensure safe power availability for all subsystems.

While the motion of industrial robots is typically governed by pre-defined trajectories and rule-based control, humanoid robots are increasingly driven by AI-based control algorithms. Distinct learning paradigms are generally applied for locomotion and manipulation.

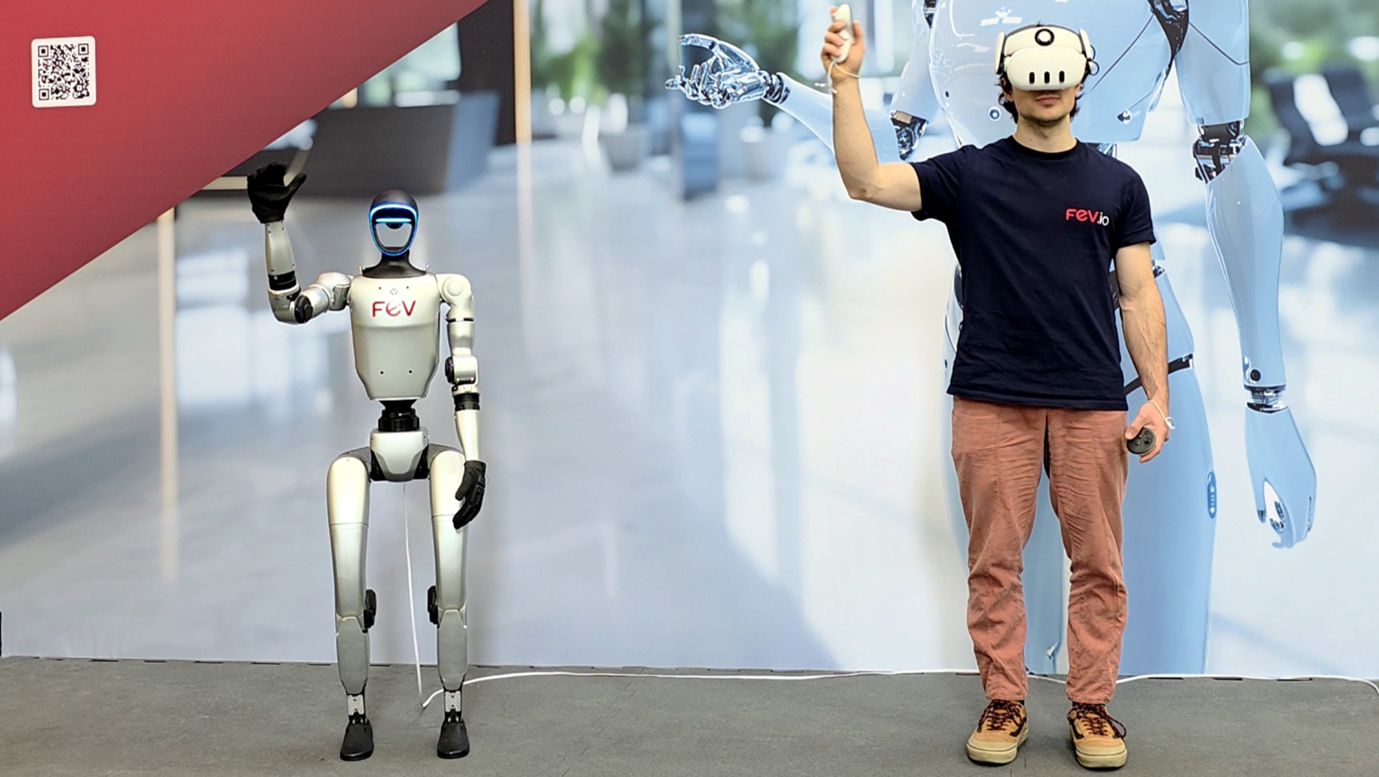

Locomotion is commonly learned in simulation through trial-and-error using reinforcement learning, enabling humanoids to acquire robust and adaptive walking behaviors. In contrast, object manipulation is often achieved via imitation learning, whereby neural networks are trained on teleoperation data collected from the robot performing task-specific demonstrations.

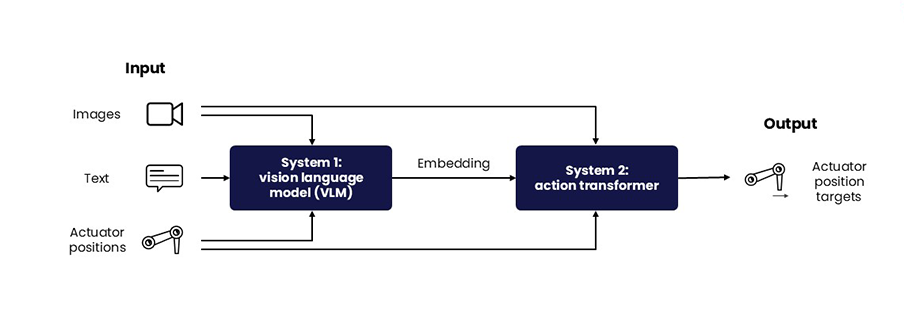

The orchestration and sequencing of multiple tasks are typically handled by vision-language-action models, frequently structured according to a “System 1 / System 2” architecture (see Figure 3). In this framework, the System 1 model processes visual and textual inputs and maps them into a shared embedding space, while the System 2 model translates these embeddings into concrete joint-level control targets.

A range of safety measures is currently implemented in humanoid robotics. Traditional approaches include remote emergency stop systems and physical emergency stop buttons integrated into the robot, as well as work cells that separate humans from humanoid robots using light curtains or physical barriers.

The industry is increasingly shifting toward physical action safety measures. These include:

In parallel, AI-related safety measures are gaining importance. These encompass content safety, which prevents the generation of harmful or inappropriate conversational outputs, and semantic action safety, which enforces compliance with physical and contextual constraints, for example, ensuring that robots do not perform unsafe actions such as pointing a knife toward a human.

In an upcoming edition of our newsletter, insights into the FEV Bot and the realization of initial use cases, such as teleoperation shown in Figure 5, will be shared.

FEV has supported leading humanoid robotics companies through strategic market advisory, technology consulting, business strategy development, cost and value management, and comprehensive benchmarking activities. Building on its expertise in humanoid robotics and engineering, FEV is now actively fostering the growth of the humanoid robotics ecosystem through the implementation of concrete use cases.

Contact us to learn how our robotics expertise can support and accelerate your organization’s ambitions: solutions@fev.io

Authors:

Dr. Dominik Boemer, PMP (https://www.linkedin.com/in/dominikboemer/)

Sven Teichmann (https://www.linkedin.com/in/sven-teichmann-823bb413a/)